by Duncan Yoon

Fall 2022

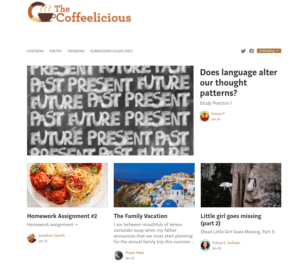

One of the things I like the most about some of the Gallatin concentrations that I advise is that they combine a practical skill set with significant critical thinking. This was in the back of my mind when I started using StoryMaps in the classroom; it gives the students a chance to gain some new technical knowhow while at the same time do some heavy conceptual lifting. I also like how its platform encourages the students to present their narratives and/or arguments in a multimedia format. So instead of writing the same old end-of-the-semester term paper, something that can easily disappear into the recesses of a file cabinet after they finish, the students now have the start of a digital dossier—something they can easily share with friends, family, and even potential employers. Simply put, when asked what they did in that crazy sounding Gallatin seminar, they can send over an easily accessible piece of their NYU career.

See student Emilie Meyer’s Storymap project, Sculpture of the Absurd: Alberto Giacometti and Samuel Beckett.

StoryMaps is a platform that is meant to narrativize maps built using the extremely robust ArcGIS program. However, using StoryMaps as a substitute for a traditional term paper does require some extra work. Throughout the semester, but especially at the beginning, I feature a series of workshops in conjunction with the Digital Studio at Bobst Library in order to give the students a primer on the software. In the syllabus, I identify this as an introduction to the Digital Humanities. These workshops introduce the students to ArcGIS by teaching them how to create map layers using existing data sets as well as create simple maps themselves. While this introduction is only dipping a toe into the deep water that is ArcGIS, it does help demystify one of the most sought after digital competencies in the workplace. My hope is that after this introduction, students will be motivated to take a whole class on ArcGIS, which would cement practical skills that they can use not only while they are still at NYU, but also after they graduate.

I could even envision a year-long course that explicitly combines ArcGIS with one of my courses, Thinking Diasporically: Postcolonialism and Migration. Because one of the main themes of this course is mobility, it would sync nicely with the mapping and visualizations provided by ArcGIS and StoryMaps. In order to do it correctly would require some team teaching so that both the practical and conceptual expertises are conveyed effectively. By having the sequence be a year long, with one semester devoted to the course material and one semester devoted to acquiring digital competency, I think that the final projects could be easily incorporated into an end-of-the-year showcase wherein the students present their projects to Gallatin and the wider NYU community. Such an in-depth process would also give students a real chance to wade into the complexity of their concentrations by equipping them with both the conceptual and digital tools necessary to not only grapple with big ideas, but also to express themselves and their ideas in a way that resonates with our increasingly digital world.

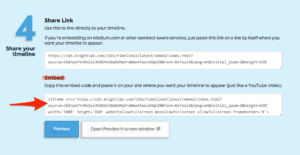

Explore more Storymap projects in the ArcGIS Storymaps Gallery, find out how to access Storymaps at NYU, and contact Jenny Kijowski at jenny.kijowski@nyu.edu to find out more about how you can use StoryMaps in your courses.